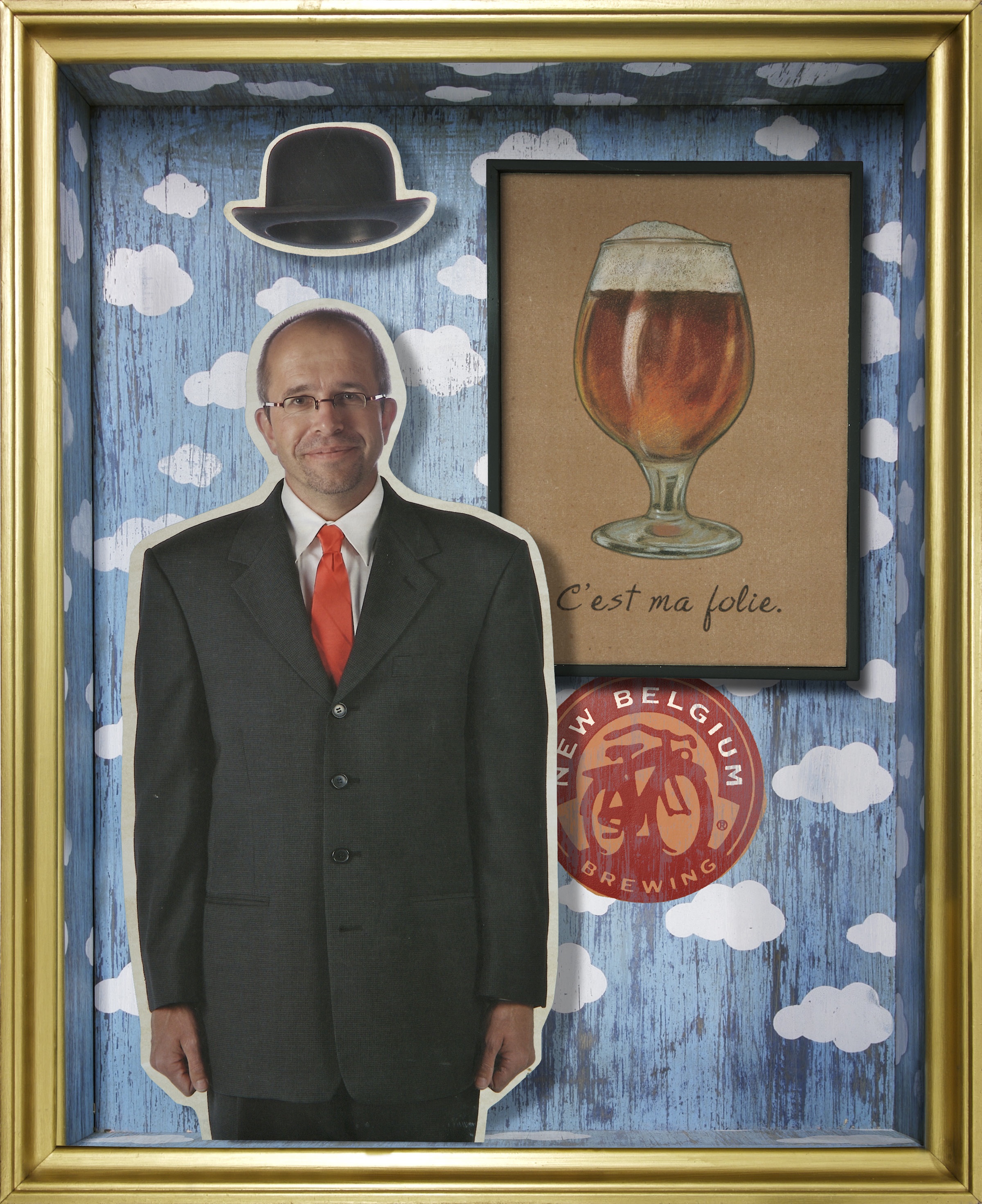

Belgium native Peter Bouckaert was working at Rodenbach, with plans to open a brewpub. However, a chance encounter at the Craft Brewers Conference in Boston led to him landing the brewmaster’s job at New Belgium Brewing Co.. I recently caught up with Bouckaert by phone, where we discussed his background and approach.

How did you become so interested in beer?

It was probably because of my studies. I studied biochemistry, but there was a direction at university that specialized in beer, and they always seemed to have so much fun.

Where did you go to school?

Universiteit Gent in Belgium.

How useful was your education for what you’re doing now?

I’m an engineer with specialization in brewing and the fermentation side. It was a good basis. We saw a whole bunch of other stuff like mechanics. You learn about pumps, learn to program, marketing and sales are all applicable.

What’s your first beer memory?

I liked to go to visit my grandma, who lived alone at that point. Her husband died when I was four, in ’69. When we went over there we played with caps from beer. They had an old bar. I never saw it open. We made castles with beer caps.. She always gave us table beer, it was 2.5% alcohol. The first brewery I worked in we made four different types of table beer; it’s something you drink at lunchtime.

What was the first beer that you brewed?

San Gilbertus. We were making beer with sorghum, but that wasn’t very good. When I was in brewing school, Nigeria stopped importing grains, so we had to try other things. It was a bottle conditioned tripel, named for professor Gilbert Baetslè. He was quite proud because it was the first time a beer was ready by November for the symposium in December.

What was your first beer related job?

I did beer delivery. I worked a student job in beer delivery for guys who are now called ABI. At that time it was Interbrew. I worked in a distributorship. I was going from bar to bar delivering Stella, Leffe and Coke. We went to all kinds of bars in Belgium, including big bars where we dropped by 36 kegs every two days. I was 19 or 20.

Where did you grow up?

A little village called Heule. It’s very close to France and very close to Bruges. It’s a Flemish speaking country close to the coast. It’s a brewery area and close to Rodenbach, which was my first job in beer.

Would you say that you have any brewing mentors?

The key guys in my life were at the first brewery where I was brewing, Brewery Zulte. The brewmaster – Anton Lietaer – knew that I went to school to work in beer, so when I was cleaning the tanks, he brought me to help with problems. I still remember he had one phrase he always repeated, and a couple years later they closed the brewery in Zulte. At that point it belonged to Kronenburg, which became Newcastle, which became Heineken. He moved on to the biggest brewery, and he’s still there now. He always repeated the same phrase: “At certain points you need to take distance from the past.” What he meant is that you need to create a break in beer process so you don’t carry over infection. This involves boiling, Pasteurization and filtration.

How did the opportunity come about for you at New Belgium?

Dave Rose, who’s in the hop business in Oregon, was visiting Rodenbach with friends. He said you should come out and speak at Craft Brewers Conference in Boston. Rodenbach wasn’t interested in sending me. The next year they offered to pay for my flight and hotel, so Rodenbach didn’t have a problem then. I later learned that the company that paid for two Belgian brewers to attend was New Belgium. I met Kim and Jeff at Craft Brewers Conference in Boston. They said they were looking for a Belgian brewmaster. We had just started a brewpub. It took us a couple of days of traveling before calling back to Kim to see if she was serious. She was. We said, “Okay, we’ll be there in two days.”

What happened with your brewpub?

I left it with a friend, a bar owner. There was no brewery, so we brought in some equipment, brewing knowledge and bar knowledge…I just looked it up. it closed out in 2002.

What distinguishes New Belgium beers from other breweries?

Originally, when I started here, I was surprised on the focus on quality. At that point, we were at 56,000 barrels, so we were really small, but we already had eight people in the lab at that point. At that point we just moved into the current location. They had overstretched, so we had a bunch of issues in the beginning. I could touch things here and turn them into gold. They’re one of the first craft brewers who focused on sales…Kim was doing all the sales at that point. Also, the way we built out the brewery was very dynamic. We can do whatever we want to do. I have a meeting on expansion, bringing more tanks. We always focus on staying very flexible. If you asked me last year at this time, I would have thought we’d never have an IPA. You never know what this brewery will be a year from now. That’ a huge strength for New Belgium.

What styles of beer do you typically enjoy drinking?

I hate styles. Styles are limiting the creativity of the brewery. Styles are a box. You taste the beer for the merits for a beer. You don’t taste the beer for the style…If you go to Belgium, you see a beer menu, they don’t make a distinction between pale, dark and sour.

How do you feel about collaborating with other breweries?

That is fun. I’ve done that pretty much from the get-go. It wasn’t really like it is now. When I started here, I started brewing at a brewpub in Boulder also. I worked with Tomme on Mo Betta Bretta. For the American Craft Beer Week, we blended a beer with three Fort Collins breweries. I’m working in the fourth quarter with Allagash, with Jason Perkins. We also have a partnership with Elysian. It’s either my brewery, my ingredients, and Dick comes over here, or it’s his brewery and his ingredients. I like what U.S. brewers are doing with this, because it’s the nature of the industry. We’re not the big ones. We’re not fighting and back stabbing each other. Also, if you work with another brewery, you deal with different equipment and completely different views on beer. I’d love to do more of it.

What are some other breweries that you really respect?

It’s always a mixture of the brewers, the beer and the brewery that leads to the appreciation of the beer. I used to say Hapkin. The guy finished the year before me. It was a small crappy brewery but he made something excellent out of it. Somebody took it over and said they’d keep all the employees, but they ended up closing it less than a year later.

Orval Shows you a very good thing about Trappist styles. It’s a beautiful beer, a beautiful brewery. Jean-Marie Rock and I have the same sense of humor.

If I switch to the U.S., probably talk about Russian River. Vinnie and Natalie are key elements in the U.S. brewing scene due to their personality, enthusisasm, and the beer they brew is beautiful. I always advise them against going to a production facility, but they’re going to have a hard time and a lot of fun.

What’s the newest recipe that you brewed, and what was your approach?

The most recent was a Berliner Weisse. The approach? I was intrigued by German brewing, which was always boring to me. They make very good beer, but don’t have creativity. Then I drank Schultheiss. Lactobacillus, Brettanomyces, boil in the mash, that’s crazy. I found some literature from Professor Frank-Jürgen Methner at the University of Berlin, by accident got introduced to him in Houston. He was surprised we even knew his name…It was very intriguing. We never really had an opportunity to do that, since it didn’t fit with New Belgium. I met some other guys and went in November to Berlin. We tasted 26-year-old and 23-year-old, but that one was not as great. By accident, I came back from Berlin, but those guys came over here and brought me Schultheiss, and it had Lactobacillus and Brettanomyces in there. I never thought I would make a German beer. They used to make Berliner Weisse very strong, 7 to 8 volume percent, which they call Champagne Weisse. What I’m making is a Champagne Weisse. It’s not milky, and no diacetyl. We’re going to wait 26 years, but that’s okay. We brewed it a month and a half ago. Bottle it in two weeks and age it so the Brett character develops.

If you could only drink one more beer, what would it be?

I’m really a butterfly. It would depend on the moment, whether I’m in a cold environment. The last one in my life, that would be tough. I probably pick Orval again. I like the dryness, the Brett, the hoppiness, and it doesn’t need to be too old for me.

Leave a Comment