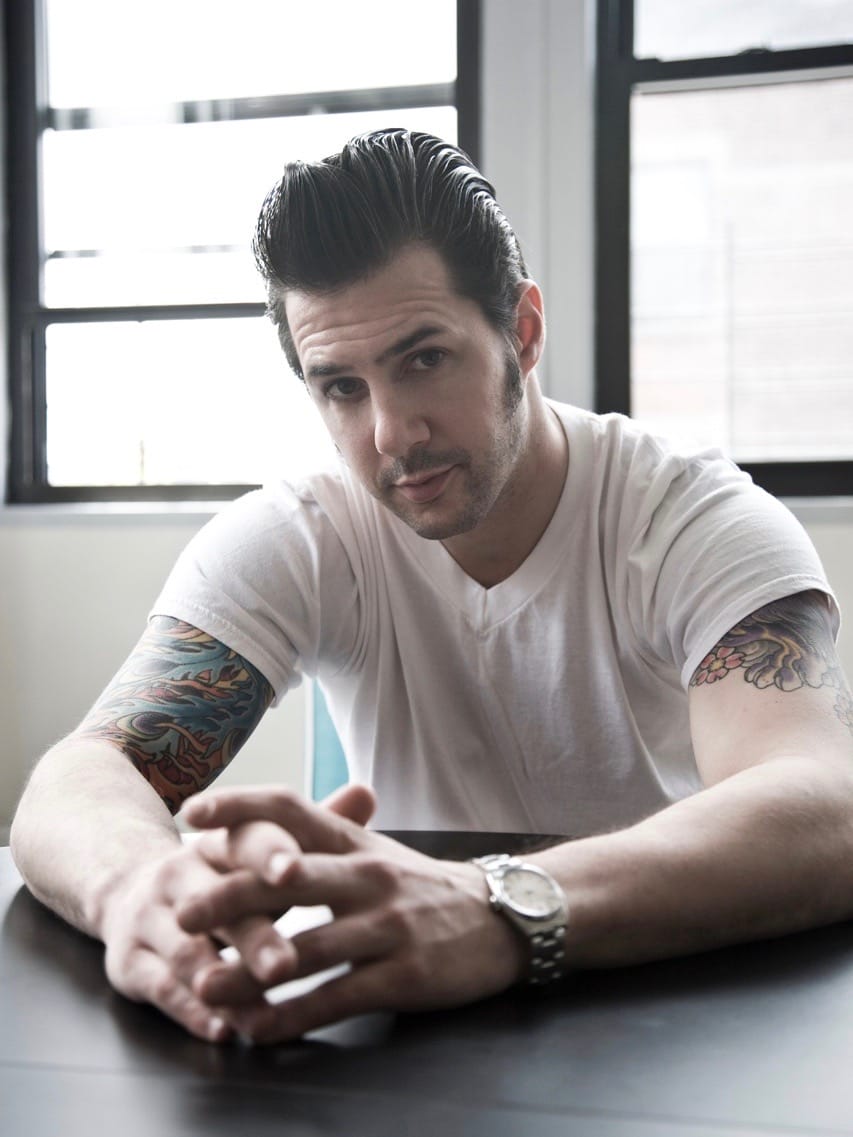

In many ways, Johnny Iuzzini has become the quintessential 21st Century pastry chef. He’s spent the past decade leading top tier departments for internationally renowned chefs Daniel Boulud and Jean Georges. The native (upstate) New Yorker is currently executive pastry chef at Jean Georges, Nougatine and Perry Street in Manhattan. He authored “Dessert Fourplay: Sweet Quartets from a Four-Star Pastry Chef,” and given the chance, will write more cookbooks. However, his most high profile role yet is as the head judge of Top Chef: Just Desserts, where he’s become the leading arbiter, protector and proponent of what his profession can and should be. We recently met on the roof of a building near downtown L.A., where he delved deep into his background and approach.

What are some desserts or pastries that you really remember loving as a kid?

I grew up upstate New York, so my mother always had a big garden out back. And part of it was because she just liked to be outdoors. The other part of it, we just weren’t a wealthy family. We ate a lot of what we grew. My dad was always a hunter, so there were times in winter time when the only proteins we had was what he hunted for…My mother was always good with a garden, so we always had peas and string beans and rhubarb. And we had Concord grapes on a trellis, so rhubarb and Concord grapes are two of my all-time favorite flavors in the world. It’s funny because we’re the only part of the country that gets to experience that in its freshest form. For me, those are the kinds of things that I really love.

Do you remember the very first pastry that you ever made?

We were latchkey kids, my brother and I, so we would spend a lot of time riffling through pantries and seeing what we could find. Although my mom did her best, she wasn’t a great cook, so there were a lot of TV dinners in the freezer for us, and a lot of box mixes. I thought I was cool with a box mix and finding something in the pantry to mix in, so I would take a box cake mix and find cool nuts, or something else, or chop up licorice sticks. My dad was really big into licorice, so I’d put licorice in there. Or I would doctor up essentially store bought mixes. That’s my first memory or really having some success. Because those box mixes are bulletproof. Those things are awesome. People will give them shit, but they’re really well made. They’re engineered to always work, and to be tasty, and to be moist. You can pick at them all you want, but I would probably guess a pastry chef had something to do with the creation of those recipes.

Has anybody else in your family worked in restaurants?

I have a bunch of chefs in my family. Two of my cousins are chefs. My father owned a restaurant with my uncle before I was born. They all worked in the restaurant, both in the front of the house and the back of the house. It was never a goal. They never pushed me or talked to me about owning a restaurant. By the time I was born and old enough to know what was going on, my father was in plumbing and heating – blue collar, very much so – and my mother was a wildlife rehabilitator. Neither one of them were in a restaurant.

What was your first restaurant job?

I grew up in the Catskills. It was very rural. We rode our bikes everywhere we wanted to go. I grew up between a corn field and a sheep farm. There wasn’t a whole lot to do…When it came time to get a little older and you wanted to start dating, we didn’t get allowances. We weren’t that type of family. If we wanted something, we had to do chores to get money…And the closest things were country clubs up there, like golf clubs. [My friends] all went and got jobs as caddies. They were really cool, driving the golf carts around, and had these cool jobs. The only job left was a dishwasher in the restaurant. I took a job as a pot washer, and every day after school, I would ride my bike to the golf club and wash pots, and come home smelling like shit, and disgusting, and my shoes would be rotting. At first I hated it, but the chef took a liking to me, and little by little, I’d peel carrots or let me use the deli slicer, and it taught me about food and inspired an interest in me.

How did the River Cafe opportunity come about?

It just so happened the florist at the restaurant I was working at, at the time, was also the florist at the River Café in Brooklyn. So Brooklyn’s about an hour and a half, two hours away, from where I grew up. She’s like, “Why don’t I bring you to meet the chef?” I had just graduated high school, so she brought me there and he hired me on the spot. He said, “Okay, we’ll hire you for garde manger,” so I was 17 years old, working garde manger for River Café.

Growing up in the Catskills, we never got whole animals. Everything came fabricated already, by companies like Sysco…Once I got to high end restaurants like River Café, which was really highly regarded at the time, all the all whole animals were coming in…My mother was a wildlife rehabilitator, so I grew up feeding and rehabilitating animals all my life. We had raccoons the size of your hand, and I’d be feeding them with baby bottles before their eyes were even open…Any kind of animal that was hurt in the wilderness, or whose parents were killed, [my mother] would raise it and then release it into the wilderness when they were ready. So I grew up a huge animal lover. It was like a farm. We had pigs, we had a horse, any kind of animal you could think of was on our property – vultures, fox – that we would nurse back to health as a family and then release them. Then to get animals in and have to cut their heads off or fucking pull their eyes out, I couldn’t do it. Every time I had to kill lobsters, I would say Hail Marys and freak out. It really affected me.

There was an amazing pastry chef who worked there, and my shift was a.m., garde manger, I would work all morning doing these things, threading chives through waffle chips and stuff. I was like, “This is not for me,” but the pastry chef would be out at night making bridges out of chocolate, and butterflies, and making cakes, using scales and grams. The only thing I knew from chocolate was caramel candy bars growing up, and Hershey’s kisses. I didn’t understand, so I was really intrigued. I would work my shift all day long in the kitchen, and then work for free, as long as he would let me help, every night. And then one day, he said, “You should be a pastry chef.” This was also after an event where the chef in the kitchen, I was looking over the brulees for the pastry chef, and he said, “What are you doing? That’s not your job.” I said, “The reason why they do this…” – I thought he actually wanted to know what I was doing, and not questioning what the fuck I was doing – he closed my arm in the oven door. I’m like, “I’m done with this.” Then the pastry chef said, “Come work with me.” So I switched, and for me, the whole love of being a pastry chef is you could be much more creative in the spectrum of what a pastry chef is, as well as it’s much more precise. You could have five different chefs making a soup, essentially with the same recipe, and you’ll have five different soups. When you have pastry, everything’s so organized, so precise, that there’s very little room for inconsistency, and that’s what I love. I love precision…[Also] pastry’s always been a jewel at the end of the meal, a treasure, a bonus, a gift, so people are much more apt at taking chances and being more lighthearted when it comes to desserts, and I like having fun with that.

Did you get what you wanted out of going to CIA?

I had the benefit of having experience going into it. A lot of kids came right out of high school…The CIA demanded six months experience, but it could be in anything, counter work at a donut shop. I had an advantage over some people, but my disadvantage was that I was still in the mentality that I had to be there, and I wasn’t paying to be there. Looking back now, I wish that I had been a bit more focused. I tend to be super hyper and all over the place, and very social, and I think that probably got in the way because of my immaturity at the time. I think the school is great – and what people don’t realize, especially the students coming out of there – they come out of there thinking they’re a chef. You come out of there, you have a base foundation to now build on, and then it’s up to you. The school gives you the structure you need to become a great chef. It doesn’t make you a great chef.

Are you still associated with CIA? Do you go back to teach?

I haven’t. I’ve only been back to the school a couple times, and that’s nothing against the school, it’s just my schedule is tough. I tend to do a lot with the schools in New York, like FCI or ICE. I’m a big proponent of people going to school. Like I said, it provides you a foundation. But a lot of people, a lot of great chefs, never went to school. And that’s not to say you don’t need to go to school. People make their own decisions, but schools serve a purpose.

How did the opportunity come about with Jean Georges?

I graduated school, and when I did my externship from school, I worked for a pastry chef named Lincoln Carson. He’s now the corporate guy at the Michael Mina Group, and he’s a young guy. He actually brought me to buy my first street motorcycle. I grew up on dirt bikes, and I never had a street bike, but Lincoln and I went, and we bought my motorcycle together. He’s been a good friend ever since. He’s a great pastry chef, very inspiring, so when I finished my externship and was finishing school, Lincoln had formerly worked for Francois Payard at Le Bernardin, and Francois was now at Daniel. Lincoln’s like, “You need to go work for Francois.” So before I finished school, I started interviewing with different people, and when I went to Francois, he said, “Okay, you come spend a day with me.”

I come spend a day with him, very scary guy, intimidating guy. Not only is he big, but he’s got these piercing blue eyes, he just stares you down and it feels like he’s looking into your soul. You feel guilty no matter what you’re doing. I was talking to him and spent the day working for him, and at the end of the day, I was standing up, very military style, hands behind my back, like “Yes, chef. Yes, chef. No, chef,” afraid to say anything else. He’s like, “Okay, you start Monday.” I said, “Chef, I’m still in school.” He’s like, “Why did you come here? You come to waste my time? You fucking guys.” He screamed at me, and I’m like, “Chef, I haven’t graduated yet. I want a job when I graduate.” He’s like, “Okay, well now you have to come every weekend until you graduate.” I had to come every weekend, I graduated on a Friday and had to start work on a Saturday. It was like that. And I stayed with Francois for three and a half years at Daniel and was his opening sous chef at Payard.

Then I left to take a trip around the world. At the time, I was doing both Payard and Daniel, because they needed help at both places. It was 16 hour days, six days a week. It was rough. I wasn’t making a lot of money, even working two jobs, so I was also working in the clubs part time. The clubs were actually what gave me enough money to support myself and follow my dream by working with these great chefs. Part of the tradeoff of working for Daniel or anybody else, they’re big houses with great reputations, and great to have on your resume, but on the flipside, they know that too and they’re not going to pay you a whole lot to be there. There’s a stack of people who want to work there.

What were the clubs you were working at, and what were you doing?

I was always out anyway. I wasn’t a big drinker. I didn’t smoke. Cooks would always go into bars after work, and I wasn’t really into bars at that time. I’ve always loved music, so I would go to these big clubs, and I loved to dance and to see the culture of what the New York club was really about. I met a lot of crazy people. I’m one of those people – I’m social – it’s easy for me to grab a crowd and bring a crowd with me. I think they realized that, so they’d say, “We’d love to have you host a party,” or promote a party. I would go to these clubs where, at the time, it was 20 bucks to get into a club, so people would pay – if they were on my guest list – they would pay 15. The club got 10, I got 5 per head. So it was a way to make a lot of money for hanging out. So I did that for a couple years at different clubs, like the Roxy, Tunnel, Sound Factory, big clubs. I was hanging out at the Limelight all the time.

Then there was some of allure to me about working the door at a club…At the time, when you’re so caught up in that world, you’re like, “The doorman controls it.” I ended up getting a job working the door, Tunnel inside door, Sound Factory outside door and Roxy outside door. Essentially you’d have 1000 people outside the door on a busy Friday or Saturday night, choosing people, “You can come in, you don’t come in.” Guys would come in poorly dressed, and I’m like, “Sorry guys, you’re all guys, you’re not dressed, you don’t have any girls with you.” It would get bad sometimes. They’d take a swing at me. Bouncers would take care of that issue, but for the most part, there was something crazy about it. I would make more money two nights working a club than I would make six nights working in two restaurants.

All the while you kept up your pastry duties?

All the while I kept up two lives very separately. I didn’t drink or anything, so I would just be tired a lot, but I would never be messed up. That went on for quite some time. It got to a point where I was working at Payard, I had to be at Payard at 4 o’clock in the morning, so from 4 o’clock in the morning to 5 or 6 at night, I would work at Payard, say on a Friday. I would come home from work at 6 o’clock at night, go to sleep for a couple hours, get up because I had to be at the club by 11 o’clock at night, work until 4 o’clock on a Saturday morning, wake up, go to Payard and do the same thing, go home and sleep for a couple hours, get up, because I had to be at the Roxy by 11 o’clock or Sound Factory by 11 o’clock, and work from 11 p.m. to six in the morning there. Those were like cabaret clubs, so they wouldn’t close, the door would be open until noon, straight through, so I would go on the dance floor, dance until 2, go home and sleep, then have to be back at Payard at 4 o’clock in the morning. That went on for years, to the point that it finally broke me down. I got pneumonia, I was tired.

Plus, I didn’t understand how I could go and care so much about the work I did in the restaurant, work so hard and take on this extra job to allow me to follow my passion, and then be treated so bad. I was the only American for a long time. I learned French out of necessity because I felt like they were always talking bad about me and trashing me. Francois was like, [quotes Payard in French], which means, “Learn French right away or get out.” All the cooks were brought in from France at the time, so it was hard, and I was young and insecure, so I became very competitive with myself. I didn’t care about anybody else, but I wanted to be better and not get yelled at for the same thing twice. That became my mantra, “Never give them the option to yell at me for the same thing twice,” and that is what propelled me to get better on a high speed rate, out of necessity. I would come to work every day with an upset stomach worried about what I’d get yelled at about. That’s a hard way to live, and that’s a hard way to learn, but it pushed me hard to become better, fast.

After leaving Payard, you went to work for…?

After Payard, I was burned out. Everybody would be burned out. You work like that, two jobs plus a club life, forget about it. I was fried, and I decided to give notice at both places and leave. Daniel called me into his office and was like, “Well what are you doing? Where are you going?” “I think I’m going to travel around the world. Everybody tells me that’s what I should do. I’ve got to get out of here.” He’s like, “Well, where are you going to go?” I’m like, “I don’t know.” I was just going to buy a couple tickets. At the time, you could buy open tickets, the countries, and then fill ‘em in as you go. Daniel Boulud was like a second father to me. He had seen me grow for four years under his umbrella, and he’s like, “Alright. I’ll make you a deal. I’ll give you $10,000 right now. You go on your trip” – at the time he was getting ready to close the original Daniel, reopen it as Café Boulud, and then move Daniel to the old Le Cirque space on 65th Street. I said, “Deal.” He said, “It will come out of your pay when you come back. You’re going to pay me back, but rather than pay on credit cards and get crushed by interest, there won’t be interest, you’ll just pay me back.” I said, “Fine.”

I left. I got on a plane from New York to Hong Kong to Australia to Thailand to Russia, Czech Republic, Vienna, then Italy, France, Spain, Switzerland, Germany, Holland, Belgium, London, New York. Seven or eight months, just backpacking, staying in hostels. I did the world’s highest bungee jump in Switzerland. I jumped out of a plane, skydiving in Australia, and found myself working anywhere I could work. I ended up getting stages, working for Pierre Hermé at Ladurée in Paris. I worked at the Hotel Paris in Monte Carlo, Patisserie Chereau in Nice, I worked for Francois’ parents in Nice. Anywhere I could find, but the trip was just to go find myself. I kept finding myself going to pastry shops all around the world – “Please can I work for free for a day?” – not being able to communicate other than saying, “I want to work with my hands.”

How were the responses?

A lot of doors slammed in my face, but a lot of people saw that I was genuine and I just wanted to work. I didn’t care if I was doing dishes. If I was doing dishes, I could still watch what other people were doing. I didn’t expect to be paid. I knew I wasn’t going to be paid. I did that for eight months all around the world, came back, opened up Café Boulud as sous chef, then opened up Daniel as sous chef. Then when the pastry chef left, when his Visa was up, Daniel promoted me to executive pastry chef at Daniel, and I was 26 years old at the time.

How do you think that trip affected how you view pastry?

I’m afraid if I hadn’t taken that trip, I probably wouldn’t be a pastry chef today, because I was so burned out. I needed to learn more about myself, and by removing myself from the situation, from New York – because if you’re in New York, you go, it’s nonstop – by leaving the country and going around the world, I learned a ton about myself, I learned about humility, I learned about how much we as Americans take for granted. Coming back, I came back very focused and very driven and knew who I was and what I wanted to be, and why. I don’t think I knew that until that point.

What continues to inspire you?

Blog Comments

Cayenne Room

July 19, 2011 at 4:45 PM

Great insider account of the road to being a chef. Thanks!

cheft

July 17, 2011 at 7:22 PM

i love you JI but Just Desserts is a joke. if thats the way pastry is rep’d then the truth is that pastry are a bunch of whining bitches; then point taken. i know this not to be true, i have great respect for pastry and the people who do it. maybe it was the editing. thanks and keep makin cookies. lol